Many of the world’s prime forestry end up as furniture, flooring and paper in an illegal logging trade that, until now, has been difficult to tackle due to the opaqueness of global supply chains. Now WorldForestID, a new data project from The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the US Forest Stewardship Council, hopes to make illegal logging a thing of the past.

How do you protect a padauk tree in Gabon, central Africa, from illegal logging? Bore a sharp metal tube into its dark red trunk. In a pioneering new conservation project, specially trained samplers drive the gadget called a Pickering Punch into a living padauk tree at waist height. The precious sample they extract then makes a long journey to scientists at Kew Gardens in south-west London for analysis.

Along with organisations including the Forest Stewardship Council in the US, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is part of WorldForestID, an international effort to stop the fraudulent timber trade. This is the wood that ends up as furniture, flooring and paper, but whose identity and provenance is little understood with existing databases of geo-referenced wood samples being limited and documentation poor.

According to the European Union, between 20 percent and 40 percent of the global timber trade comes from illegal sources, and costs the governments of developing countries between €10-€15bn [US$12bn to $18bn] a year in lost revenues, while decimating native forests, reducing habitat for wildlife and depressing world timber prices. Rosewood alone comprises 35 percent of the monetary value of confiscated illegal wildlife trade, according to WorldForestID.

WorldForestID is trying to tackle this by answering two questions, says Dr Peter Gasson, wood anatomist at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: What is the identity of the wood and where was it grown? “First of all, we need adequate reference wood samples from which to derive data, and then we can address these two questions,” he says.

The project is complicated by the fact that trees are harvested in one place, transported through one or more countries, and only then processed into manufactured products: oak furniture and flooring imported into the USA and Europe, for example, often comprising several species of white oak from North America and the Russian Far East.

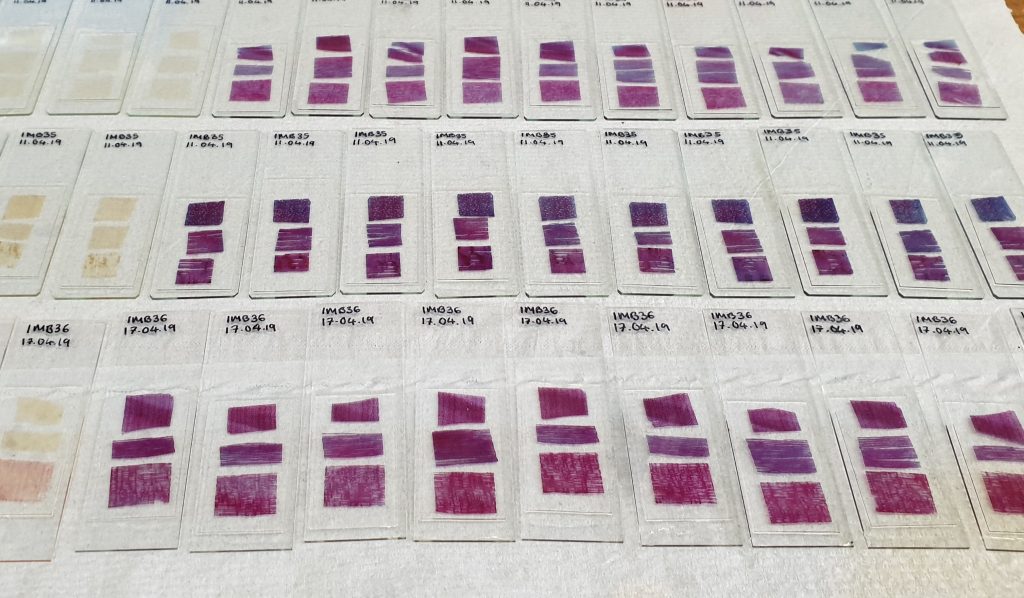

Back in Gabon, the Pickering Punch has worked its magic and the sample is dried and packed off to Kew’s Plant Quarantine Unit, where it’s inspected for contamination. It’s then frozen at -40 degrees centigrade for 72 hours to kill any invertebrates with the sample’s origin. Then the process of identity verification begins.

It’s relatively easy for an expert to identify the genus by eye or hand lens, or using a microscope. But like the forests they’re trying to protect, the population of expert anatomists is in decline. Automated machine learning is being developed by the team to meet this human shortfall. Routes to identification include chemical analysis, DNA sequencing, and stable isotope ratio analysis, which can shed light on the environment the tree has grown in, as well as its age.

To counter the risk of samples being given fraudulent geo-locations, the WFID smartphone app used by samplers in the field, has a time-stamp feature, and GPS coordinates that can’t be overridden.

Getting the data is one thing. Then comes the challenge of getting traders, legislators, scientists and timber consumers to embrace science-based wood authentication. WorldForest ID is optimistic about the prospects. “We envisage the day that scientific methods will be used routinely and successfully by timber traders, manufacturers, retailers and law enforcement to accept or reject identity and provenance claims on internationally traded timber and forest products, and to support prosecutions when laws are infringed,” a spokesperson says.

Author: Clare Dowdy, The India Story Agency for Sacred Groves

Images Credit: ©FSC International / Loa Dalgaard Worm and Kew

Did you enjoy this article?

Share with friends to inspire positive action.