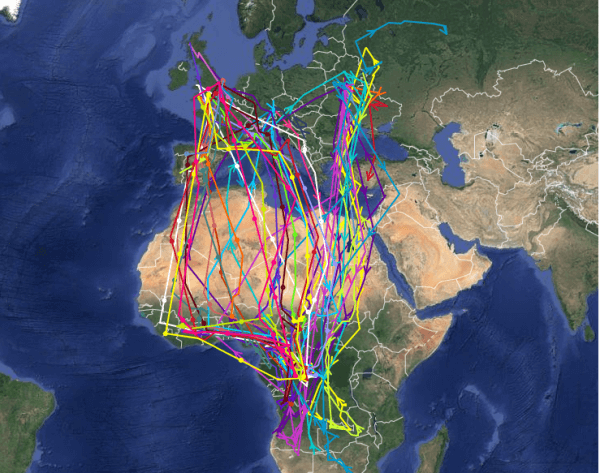

From the effects of climate change on migratory patterns to habitat erosion, avian populations are under threat as never before. Happily, citizen science is offering a helping hand.

How do you track something as shifting and ephemeral as global bird migrations? Use the might of the great British twitcher [bird watcher], that’s how.

BirdTrack is an online citizen science website, operated by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) in partnership with the RSPB, BirdWatch Ireland, the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club and the Welsh Ornithological Society that allows birdwatchers to record the names and numbers of birds seen in a specified location anywhere in the world.

BirdTrack’s community of 34,000 active users has, to date, uploaded 1.1 billion entries of data, logging everything from species location and behaviour to birdsong and mating behaviours, says the BTO’s Scott Mayson.

“We get simple entries that say ‘I saw X bird at X location’; but then we will get really precise references such as that a male was singing to a female a specific ordnance survey grid reference and it was a mating song. In our world, though, all records are useful.”

The data – which feeds into similar data inputs from the European Commission-funded Eurobird portal – allows the real-time mapping of bird migrations across the European continent and, crucially, charts how these avian flows are changing year-on-year.

“We find that some birds, such as the willow warbler, are migrating further northwards,” Mayson explains, “and that species such as the chiffchaff and blackcap which used to winter on the continent are now wintering here.”

BirdTrack’s vast data pool, Mayson adds, acts as an early warning system that species might be under threat, whether that’s as a result of global heating, pollution or of habitat destruction. “We now know that bitterns, a kind of small heron, are dwindling as their reed-bed habitats [thickly vegetated and waterlogged zones between water and land] have been drained; so there are efforts to restore these habitats that have come directly from this data.”

It’s thanks, too, to BirdTrack data that the RSPB is running mass surveys of species that appear to be under threat, including the lesser-spotted woodpecker and fabled turtle dove.

Andrew Sims, 74 and based in Lincolnshire, has been a twitcher since the 1970s and an enthusiastic BirdTracker for the past eight years. Sims enjoys a daily birding walk along the same looped route from his home and religiously submits his sightings into BirdTrack’s app as he strolls. “By submitting at the same spots every day through the years I know I’m doing my bit to help record population trends,” he says. “It feels like a service as well as a pleasure.”

Little egrets, rare when he began twitching, are now a common sight, Sims says, as his much-loved woodpeckers have slowly disappeared from his patch. He hopes that data such as his will make an argument for government interventions in climate change. “I love that BirdTrack gives you a personal record of your sightings over time as well as the bigger picture,” he adds.

An obvious risk with mass citizen science projects is spotter error: what if an unschooled birder identifies a chaffinch for a sparrow; say? BirdTrack, says Mayson, flags up an entry if a user chooses a species that is unexpected in an area at a given time of year, to make such mis-identifications less likely.

BirdTrack has seen its usership increase 23 percent since the pandemic as we feel a renewed appreciation for outdoor environments, and their feathered residents. BirdTrack has also realised, in this strange time, the potential of its data to protect both avian and human populations from disease. “We can look at the movements of reservoir species such as geese, for example, to predict where the next outbreaks of bird flu might happen,” Mayson adds.

Author: The India Story Agency for Sacred Groves

Images Credit: British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) and Eurobird

Did you enjoy this article?

Share with friends to inspire positive action.